How I Found Balance Through Real Chinese Healing Wisdom

For years, I struggled with constant fatigue, low energy, and unexplained aches—despite eating well and exercising. Western checkups found nothing wrong, but I knew something was off. Then I discovered zhengti tanwei, the core principle of Traditional Chinese Medicine: health isn’t just absence of disease, but harmony within. This shift in mindset—seeing my body as a connected system—changed everything. What I learned wasn’t about quick fixes, but sustainable, natural balance. It offered a deeper understanding of wellness, one that honored subtle signals and long-term rhythm over isolated symptoms. This journey led me to a more resilient, grounded way of living.

The Hidden Imbalance: Why “Normal” Lab Results Don’t Tell the Whole Story

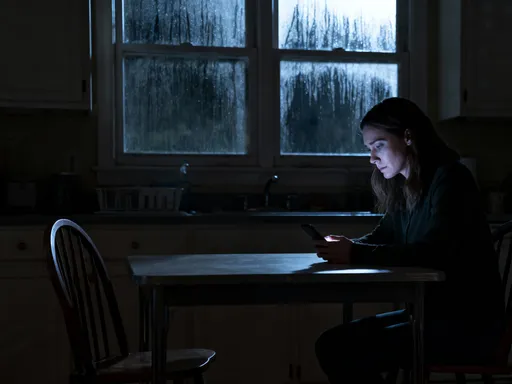

Many women between 30 and 55 know this feeling: you’re functioning, even thriving in daily life, yet something feels quietly off. You may sleep enough but wake unrefreshed, eat balanced meals but feel bloated, or manage stress without obvious breakdown—yet a low hum of fatigue lingers. Blood tests return within normal ranges, so doctors say there’s no cause for concern. But normal lab values don’t always reflect how a person truly feels. This gap is where the concept of sub-health becomes essential.

Sub-health, widely recognized in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), describes a state between wellness and illness. It’s not a diagnosable disease, but a collection of subtle signs—poor sleep quality, digestive discomfort, mood fluctuations, or frequent colds—that suggest imbalance. These are early warnings, signals that the body’s internal systems are under strain. In Western medicine, such symptoms may be dismissed or treated individually with sleep aids, antacids, or mood regulators. But TCM asks a different question: what underlying pattern connects these seemingly unrelated issues?

The limitation of symptom-by-symptom treatment is that it often overlooks root causes. For example, chronic fatigue may stem from poor digestion affecting nutrient absorption, or unresolved emotional stress disrupting hormonal balance. When only the fatigue is addressed, the cycle continues. TCM takes a systemic view: symptoms are not isolated malfunctions but expressions of deeper disharmony. By recognizing sub-health early, women can take proactive steps before minor imbalances evolve into more serious conditions. The goal is not to wait for disease to appear, but to restore balance while the body still has resilience.

Rooted in Harmony: Understanding the TCM View of the Body

At the heart of Traditional Chinese Medicine is a worldview that sees the human body as a dynamic, interconnected ecosystem. Unlike the mechanistic model that treats organs as separate parts, TCM views health as a continuous flow of energy and balance among systems. Three foundational concepts—Qi, Yin-Yang, and the Five Elements—form the framework for understanding this harmony. These are not mystical ideas, but practical models that guide diagnosis and treatment in a way that resonates with natural rhythms.

Qi (pronounced “chee”) is the vital energy that flows through the body, supporting all physiological functions. It powers digestion, circulation, immune response, and mental clarity. When Qi is strong and moving freely, a person feels energized and resilient. When it is deficient or blocked, fatigue, pain, or illness may follow. Think of Qi like the current in a river: when the water flows smoothly, the ecosystem thrives; when it stagnates or dries up, imbalance follows.

Yin and Yang represent the dual forces that govern all natural processes. Yin is cooling, nourishing, and restorative—like the body’s ability to regenerate during sleep. Yang is warming, active, and energizing—like the metabolism that fuels daily movement. Health depends on the balance between these forces. A woman in perimenopause, for instance, may experience hot flashes (excess Yang) and night sweats (loss of Yin), signaling a shift in this equilibrium. Rather than suppressing symptoms, TCM seeks to nourish Yin and calm Yang through diet, herbs, and lifestyle.

The Five Elements—Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water—correspond to organs, emotions, and seasons. Each element supports and controls another in a cyclical relationship. For example, the Wood element governs the liver and is linked to anger and springtime; Earth governs the spleen and digestion, tied to worry and late summer. When one element is overactive or weak, it affects others. Chronic stress may overstimulate Wood (liver), impairing Earth (spleen), leading to digestive issues. This model helps explain how emotional and physical health are intertwined, offering a holistic lens for healing.

Diagnosis Beyond the Symptom: The Art of Pattern Recognition in TCM

One of the most distinctive aspects of Traditional Chinese Medicine is its diagnostic approach. Rather than focusing on a single symptom or disease label, TCM practitioners assess the whole person through pattern recognition. This process involves careful observation of the tongue, listening to the voice, feeling the pulse at multiple points, and asking detailed questions about sleep, digestion, emotions, and daily rhythms. Each of these clues contributes to a comprehensive picture of the body’s internal state.

Tongue diagnosis, for instance, reveals much about internal health. A pale tongue may indicate Qi or blood deficiency, common in women with fatigue or heavy menstrual cycles. A red tongue with a yellow coating might suggest internal heat, often linked to inflammation or hormonal imbalance. Similarly, pulse reading in TCM is not just about heart rate but about quality—whether the pulse feels weak, wiry, slippery, or deep. A wiry pulse, for example, often correlates with liver Qi stagnation, frequently seen in women under prolonged stress.

This method contrasts sharply with conventional diagnostics, which often rely on lab tests, imaging, or symptom checklists to assign a disease category. While Western medicine excels at identifying acute conditions and structural abnormalities, it may miss subtle functional imbalances. TCM fills this gap by identifying patterns before they manifest as disease. Two women with insomnia may receive entirely different treatments: one with a pale tongue and weak pulse may need Qi tonification, while another with a red tongue and rapid pulse may require cooling and calming therapies.

The personalized nature of TCM ensures that care is tailored to the individual, not the symptom. This is especially valuable for women navigating hormonal transitions, chronic stress, or recovery from illness. By understanding the unique pattern of imbalance, practitioners can recommend targeted dietary changes, herbal formulas, or movement practices that address root causes. It’s a form of preventive medicine that honors the body’s signals long before crisis occurs.

Natural Levers of Change: Diet, Movement, and Rhythm in Daily Life

In Traditional Chinese Medicine, food is not just fuel—it’s medicine. The principle of “eating with the seasons” is central to maintaining balance. Each season carries its own energetic quality, and the body benefits from foods that harmonize with that energy. In winter, when the environment is cold and Yin energy dominates, warming foods like soups, stews, root vegetables, and spices such as ginger and cinnamon help preserve internal warmth. In summer, when Yang energy peaks, cooling foods like cucumber, melon, and leafy greens help prevent overheating.

TCM also classifies foods by their thermal nature—warming, cooling, or neutral—and their effect on organ systems. For example, raw and cold foods may impair spleen function, leading to sluggish digestion and dampness (a TCM term for fluid retention and bloating). A woman with chronic bloating may be advised to reduce raw salads and smoothies and instead enjoy cooked grains, steamed vegetables, and herbal teas like ginger or fennel. Similarly, someone with dry skin and constipation—signs of Yin deficiency—may benefit from nourishing foods like black sesame seeds, pears, and bone broth.

Mindful eating is another cornerstone. TCM emphasizes the importance of regular meal times, chewing thoroughly, and eating in a calm environment. Digestion begins in the mind: stress or distraction during meals can weaken the spleen’s ability to transform food into Qi and blood. Simple practices—like pausing to breathe before eating or avoiding screens during meals—can significantly improve digestive health over time.

Movement, too, plays a vital role in maintaining Qi flow. Unlike high-intensity workouts that may deplete Qi in already fatigued individuals, TCM recommends gentle, rhythmic practices. Tai Chi and Qigong are two such forms, combining slow movements, breath control, and mental focus to enhance energy circulation. Studies have shown these practices can reduce stress, improve balance, and support immune function. Even a 10-minute daily routine can help regulate the nervous system and prevent stagnation, especially for women with sedentary lifestyles.

Equally important is alignment with natural rhythms. The body operates on circadian cycles that influence energy levels, hormone production, and repair processes. Going to bed by 10:30 p.m., for example, supports liver detoxification, which peaks between 1 a.m. and 3 a.m. Eating the largest meal at midday aligns with the peak of digestive fire (spleen and stomach Qi), while lighter evening meals prevent overburdening the system. These small adjustments, rooted in ancient wisdom, can yield profound long-term benefits.

Supportive Therapies: Acupuncture, Herbal Wisdom, and External Techniques

Acupuncture is perhaps the most recognized TCM therapy in the West, and for good reason. By inserting fine needles into specific points along energy pathways (meridians), it helps regulate the flow of Qi and restore balance. Modern research supports its use for conditions like chronic pain, migraines, and nausea. For women, it has been particularly helpful in managing menstrual irregularities, PMS, and menopausal symptoms. The mechanism is not fully understood, but studies suggest acupuncture may influence the nervous system, reduce inflammation, and promote endorphin release.

Herbal medicine is another pillar of TCM, offering systemic support over time. Unlike pharmaceuticals that target single symptoms, herbal formulas are typically blends of multiple ingredients designed to address underlying patterns. For example, a formula for liver Qi stagnation might include bupleurum to move Qi, peony to nourish blood, and mint to cool excess heat. These combinations work synergistically, with each herb modifying or enhancing the others’ effects. Because herbs act gradually, they are well-suited for chronic conditions and long-term balance.

It is crucial to emphasize that herbal remedies should only be used under the guidance of a qualified practitioner. Self-prescribing can lead to imbalances or interactions with medications. For instance, certain herbs that tonify Yang may not be appropriate for someone with high blood pressure or heat signs. A trained TCM practitioner tailors formulas to the individual’s current condition, adjusting them as the body responds.

External techniques like cupping and gua sha are also valuable tools. Cupping uses suction to draw stagnation to the surface, often leaving temporary marks that fade within days. It can relieve muscle tension, improve circulation, and support respiratory health. Gua sha involves gently scraping the skin with a smooth tool to release stagnation and promote healing. Both are commonly used for colds, neck and shoulder pain, or chronic fatigue. When applied correctly, they are safe and can be integrated into regular self-care routines.

Integrating East and West: Building a Smarter Health Management Plan

The most effective approach to health often lies not in choosing between systems, but in combining their strengths. Western medicine excels in acute care, diagnostics, and emergency interventions. It can identify infections, monitor chronic diseases, and provide life-saving treatments. Traditional Chinese Medicine complements this by focusing on prevention, functional balance, and long-term vitality. Together, they form a more complete picture of wellness.

Consider a woman with irregular periods. A Western doctor might run hormone tests and prescribe medication to regulate her cycle. A TCM practitioner might identify spleen Qi deficiency or liver Qi stagnation and recommend dietary changes, acupuncture, and herbal support. The ideal path? Use Western testing to rule out serious conditions, then apply TCM strategies to address root imbalances and reduce reliance on medication over time. This integrative model empowers women to take an active role in their health.

Preventive screenings—like mammograms, bone density tests, and blood pressure checks—remain essential. TCM does not replace these but enhances them by addressing the factors that influence long-term risk. For example, managing stress through Qigong may lower cortisol levels, reducing inflammation linked to heart disease. Eating seasonally and mindfully supports metabolic health, lowering the risk of diabetes. These practices don’t negate the need for medical care—they make it more effective.

Professional guidance is non-negotiable. Women should never stop prescribed medications or self-diagnose with TCM concepts. Instead, they should seek licensed practitioners—acupuncturists, herbalists, or integrative doctors—who can collaborate with their primary care providers. Open communication ensures safety and prevents conflicts between treatments. The goal is not to abandon one system for another, but to build a personalized, evidence-informed health plan that honors both science and wisdom.

Sustaining Balance: Making TCM Principles a Lifelong Practice

True health is not a destination, but a continuous practice of awareness and adjustment. The principles of Traditional Chinese Medicine are not meant for short-term fixes but for lifelong integration. Small, consistent habits—like eating warm meals in winter, practicing 10 minutes of Qigong each morning, or noticing how stress affects digestion—accumulate into lasting resilience. Over time, women learn to listen to their bodies with greater sensitivity, catching imbalances before they deepen.

This journey requires patience. Unlike fast-acting medications, TCM works gradually, supporting the body’s innate ability to heal. A woman recovering from burnout may not feel immediate changes, but after weeks of herbal support, better sleep, and reduced stress, her energy returns more steadily. This is not about perfection, but about progress—about moving from depletion toward balance, one step at a time.

The mindset shift is profound: from reacting to symptoms to cultivating wellness. It means valuing rest as much as productivity, honoring emotional health as much as physical performance, and recognizing that true strength includes gentleness. In a world that often glorifies busyness, TCM offers a quieter, deeper path—one that aligns with nature, honors the body’s wisdom, and supports women through every stage of life.

Ultimately, the goal is not to eliminate all discomfort, but to build a body and mind that can adapt, recover, and thrive. Health, in the TCM view, is dynamic equilibrium—a flowing balance between activity and rest, nourishment and release, effort and ease. By embracing these ancient principles with modern understanding, women can create a sustainable foundation for lifelong well-being.