What Social Habits Reveal About Your Health—Backed by Science

You might not realize it, but how often you hang out with friends or join group activities can say a lot about your overall health. I started tracking my social habits last year, and the patterns were shocking. Turns out, science shows that social engagement is deeply linked to mental resilience, immune function, and even longevity. This isn’t just about feeling less lonely—it’s about measurable health signals hiding in plain sight. Let’s break down what your social life might be telling you.

The Hidden Health Signals in Your Social Calendar

Social habits are more than routines—they are reflections of inner well-being. Researchers increasingly view regular social interaction as a vital sign, much like blood pressure or sleep quality. The frequency, depth, and consistency of your connections can signal early changes in both mental and physical health. For example, a noticeable drop in attending gatherings, skipping weekly calls with loved ones, or withdrawing from community events may precede clinical symptoms of depression or anxiety by months. These behavioral shifts often go unnoticed, yet they carry predictive weight in population health studies.

Public health experts refer to this concept as “social vital signs,” a framework used to assess how integrated an individual is within supportive networks. These signs include not only how many people you interact with but also the emotional quality of those interactions. A 2020 study published in the journal Health Psychology found that adults who reported fewer than two meaningful social engagements per week had a 30% higher risk of developing hypertension over a five-year period, even after adjusting for age, diet, and physical activity. Similarly, longitudinal data from the Framingham Heart Study revealed that individuals with smaller social networks were more likely to report chronic fatigue and reduced cognitive sharpness later in life.

It’s important to distinguish between solitude and isolation. Choosing to spend time alone for reflection or rest is healthy and intentional. However, when social disengagement becomes passive or persistent—such as consistently declining invitations or allowing relationships to fade without replacement—it may reflect underlying stress, burnout, or emotional fatigue. These subtle patterns are often dismissed as normal life changes, especially during busy phases like raising children or caring for aging parents. But science suggests that ignoring them could mean missing early warnings of declining health.

Why Your Brain Treats Connection Like Nutrition

The human brain does not treat social connection as optional—it treats it as essential. Neuroimaging studies have consistently shown that positive social interactions activate the same reward centers in the brain that respond to food, water, and sleep. When you share a laugh with a friend, receive a warm message from a sibling, or feel supported during a difficult conversation, your brain releases neurotransmitters like dopamine and oxytocin. Dopamine reinforces pleasurable experiences, making you want to repeat them, while oxytocin, sometimes called the “bonding hormone,” promotes feelings of trust, calm, and attachment.

This biological response evolved for survival. Early humans relied on group cohesion for protection, resource sharing, and child-rearing. Over time, the brain developed mechanisms that reward social bonding and punish isolation. Functional MRI scans show that experiences of social rejection—such as being excluded from a group activity—activate the anterior cingulate cortex, the same region involved in processing physical pain. This suggests that, at a neurological level, feeling disconnected can hurt in ways that are real and measurable.

When social engagement becomes infrequent or emotionally shallow, these neural systems become under-stimulated. Over time, this can lead to dysregulation in mood regulation and stress response. For instance, low oxytocin levels have been associated with increased cortisol production, the hormone tied to chronic stress. Elevated cortisol, in turn, contributes to sleep disturbances, weight gain, and impaired immune function. In essence, without regular positive social input, the brain’s natural balance begins to shift, increasing vulnerability to anxiety, low mood, and cognitive fog.

For women in their 30s to 50s—often juggling roles as caregivers, professionals, and community members—this neurochemical imbalance can be especially pronounced. The demands of daily life may push social needs to the bottom of the priority list, but the brain continues to register the deficit. Recognizing that connection is not a luxury but a biological necessity helps reframe social time as self-care, not indulgence.

From Loneliness to Inflammation: The Biological Pathway

One of the most compelling discoveries in recent health research is the direct link between perceived loneliness and systemic inflammation. It’s not simply that lonely people feel worse—they experience measurable changes at the cellular level. Chronic loneliness, defined as a persistent feeling of social disconnection regardless of actual social contact, has been shown to trigger a cascade of physiological responses that increase the risk for multiple long-term conditions.

At the core of this process is the body’s stress response system. When someone feels isolated or unsupported, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis becomes activated, leading to sustained release of stress hormones like cortisol and norepinephrine. Over time, this chronic activation suppresses the immune system’s ability to regulate itself properly. As a result, the body begins to produce higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines—molecules that promote inflammation as part of the immune defense. While acute inflammation is protective, chronic inflammation damages tissues and is linked to heart disease, type 2 diabetes, arthritis, and even certain cancers.

Multiple studies, including a meta-analysis published in Perspectives on Psychological Science, have found that individuals who report high levels of loneliness exhibit elevated markers of inflammation, particularly C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). These findings hold true even after controlling for lifestyle factors such as smoking, exercise, and body mass index. This means that the feeling of loneliness itself—distinct from being physically alone—acts as an independent risk factor for poor health outcomes.

What makes this pathway particularly concerning is its invisibility. Unlike high cholesterol or high blood sugar, inflammation driven by social disconnection does not come with obvious symptoms. A woman may feel generally fatigued, have recurring minor illnesses, or notice her skin healing more slowly, without realizing these could be signs of underlying biological stress. By understanding the science behind this connection, individuals can begin to see emotional well-being as inseparable from physical health.

How Scientists Actually Measure Social Health

While emotions like loneliness may seem too personal or abstract to quantify, researchers have developed reliable tools to measure social health with scientific rigor. One of the most widely used instruments is the UCLA Loneliness Scale, a validated questionnaire that assesses subjective feelings of isolation and disconnection. Rather than focusing on the number of friends someone has, it evaluates how often a person feels left out, misunderstood, or lacking companionship. This distinction is crucial because two people with similar social networks can have vastly different emotional experiences—one may feel fulfilled, the other deeply alone.

Another key tool is the Social Network Index, which measures objective aspects of social integration. It asks individuals to report the number of close relationships they have, how frequently they interact with family and friends, and whether they belong to organized groups such as religious communities, clubs, or volunteer organizations. Studies using this index have consistently shown that higher scores correlate with lower mortality rates and better recovery outcomes after illness.

These assessments are not just academic exercises—they are increasingly used in real-world healthcare settings. Some primary care clinics now include social health screenings during annual wellness visits, particularly for patients over 50 or those managing chronic conditions. Public health initiatives, such as the UK’s former Minister for Loneliness, have used population-level data from these tools to design targeted interventions, including community companionship programs and telephone check-in services.

The integration of social health metrics into clinical practice reflects a broader shift in medicine: the recognition that health is not solely determined by genes or lifestyle choices but also by relational context. Just as doctors monitor blood pressure and BMI, they are beginning to consider social connection as a modifiable health factor. This opens the door to personalized recommendations—such as joining a local walking group or reconnecting with an old friend—that can have tangible, long-term benefits.

Spotting the Red Flags in Your Own Social Patterns

Because social decline often happens gradually, it can be difficult to recognize until it has significantly impacted well-being. Yet there are early warning signs that, when noticed in time, can prompt meaningful change. One of the most common red flags is a pattern of declining invitations—saying no more often than yes, even to events you used to enjoy. This may start as fatigue or busyness but can evolve into a habit of withdrawal.

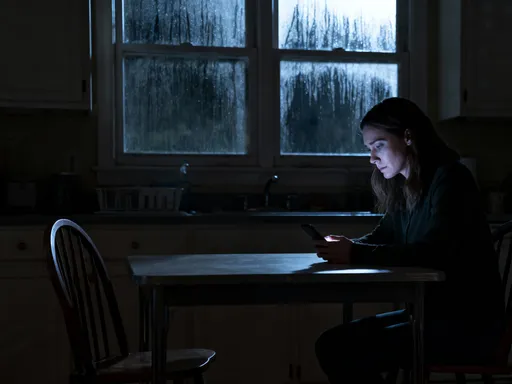

Another indicator is the shortening of conversations. You might find yourself giving brief responses to texts, ending phone calls quickly, or avoiding deep discussions. While digital communication offers convenience, it often lacks the emotional richness of face-to-face interaction. Relying heavily on texts or social media comments instead of voice or in-person contact can create a false sense of connection while leaving emotional needs unmet.

Other subtle signs include letting friendships go unattended for long periods, feeling drained after socializing when it used to energize you, or noticing that most of your interactions are transactional—such as work emails or errand-related exchanges—rather than relational. These shifts may seem minor, but when combined, they suggest a growing gap between your social input and emotional needs.

Consider the case of a 45-year-old woman who stopped attending her book club after her youngest child started school. At first, she told herself she needed the time to catch up on household tasks. But over months, she also began skipping weekly calls with her sister and stopped visiting her neighbor for coffee. She didn’t feel depressed, but she noticed she was more irritable, had trouble concentrating, and caught colds more frequently. Only when her doctor asked about her social habits during a routine visit did she realize how much her connections had dwindled. This scenario is more common than many realize—and entirely reversible with awareness and small, intentional steps.

Building a Smarter Social Routine: Small Shifts, Real Impact

Improving social health doesn’t require dramatic overhauls or large social circles. Research consistently shows that consistency and quality matter far more than quantity. A single meaningful conversation per week can have a greater impact than several superficial interactions. The goal is not to become more social for the sake of being busy, but to cultivate connections that provide emotional nourishment and mutual support.

One evidence-based strategy is scheduling regular check-ins with trusted individuals. This could be a weekly 15-minute phone call with a sibling, a monthly coffee date with a friend, or a daily text exchange with a grown child. These small rituals create predictability and reinforce bonds over time. They also serve as anchors during stressful periods, offering stability when life feels overwhelming.

Another effective approach is combining socializing with other healthy habits. Joining a walking group, attending a fitness class, or volunteering at a community garden allows you to connect with others while also supporting physical health. These activities provide built-in structure, reduce pressure to perform socially, and foster shared purpose—all of which enhance engagement and reduce anxiety.

For those who feel hesitant about initiating contact, starting with low-pressure environments can help. Community centers, libraries, and faith-based organizations often host events designed to welcome newcomers. Group-based hobbies like gardening, cooking classes, or crafting circles offer natural conversation starters and opportunities to build rapport without the intensity of one-on-one meetings. The key is to choose activities that align with personal interests, making participation feel enjoyable rather than obligatory.

It’s also important to redefine what counts as meaningful connection. For some, deep one-on-one talks are energizing. For others, being in a group setting where conversation flows naturally provides greater comfort. There is no single right way to connect—only what feels authentic and sustaining for you.

When to Seek Support—and Why It’s a Strength

There is no shame in needing help to rebuild social connections, especially after major life changes such as divorce, relocation, loss of a loved one, or prolonged illness. Persistent social withdrawal, particularly when accompanied by low energy, persistent sadness, or difficulty finding joy in activities, may indicate that professional support is needed. A licensed therapist or counselor can help explore underlying emotions, develop communication skills, and create a personalized plan for re-engagement.

Primary care providers are also valuable resources. Many now recognize the health risks associated with social isolation and can refer patients to community programs, support groups, or mental health services. In some cases, addressing an underlying condition such as anxiety, depression, or thyroid imbalance can make it easier to reconnect with others.

Seeking support is not a sign of weakness—it is an act of strength and self-respect. Just as you would consult a doctor for a persistent physical symptom, attending to your social health is a responsible, proactive choice. The journey toward greater connection is rarely linear. There will be setbacks, awkward moments, and days when reaching out feels hard. But each small step reinforces the brain’s capacity to experience joy, trust, and belonging.

Most importantly, improving social well-being is not about fixing a flaw. It is about honoring a fundamental human need—one that science now confirms is as essential as nutrition, sleep, and movement. By treating social engagement as a pillar of health, not a peripheral activity, you invest in a more resilient, balanced, and vibrant life.

Your social life isn’t just about fun—it’s a window into your body’s inner state. By treating social engagement as a health metric, not just a lifestyle choice, you gain powerful insight into your long-term well-being. The science is clear: meaningful connections aren’t optional extras. They’re essential nutrients for a resilient, thriving life. Start paying attention—not because you’re broken, but because you’re worth optimizing for.